The conservation status of any species may influence the amount of funding available to conserve it, the priority it receives from governments, and the level of public awareness and support it receives. Crucially, conservation statuses help inform decisions about wildlife trade made by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Threatened plants and animals are much less likely to be traded internationally than common species.

If you followed developments during the recent CITES Conference of Parties (CoP18), you would have seen the term “endangered species” used frequently in the media. This article about species conservation assessments will help you better understand what this term means, which is an important part of developing your own informed opinions on wildlife conservation topics.

Who says it's Endangered?

Popular articles and campaigns often use the term “endangered” quite loosely – applying to any plant or animal that is in some kind of danger. Furthermore, the Endangered Species Act is a law in the United States of America that was passed in 1973, which allows the US government to declare certain species Endangered or Threatened following their national criteria. In the rest of the world, however, the term Endangered refers to an internationally recognised conservation status that indicates where a species falls on a scale of threat from Least Concern to Extinct.

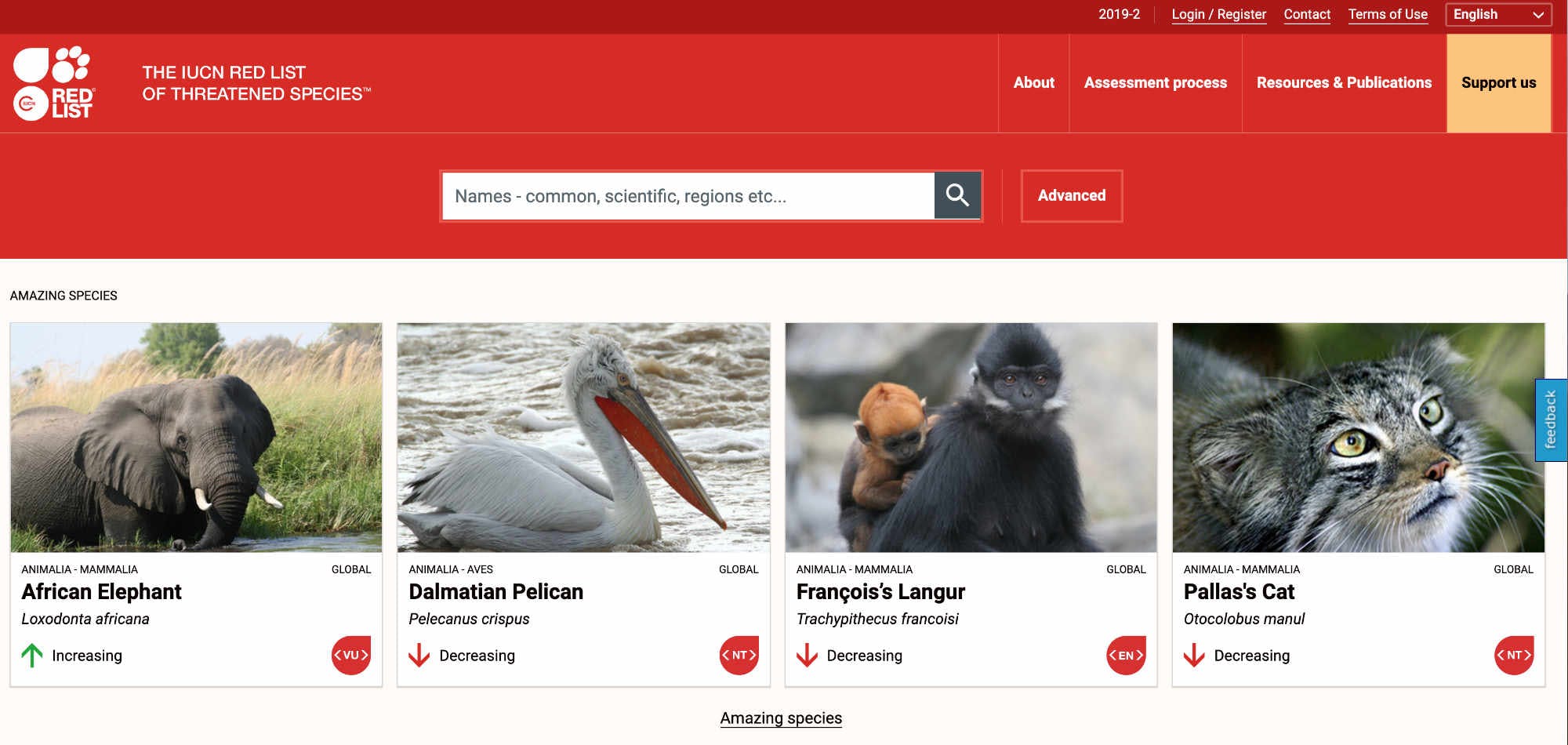

These specific terms and their definitions come from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a voluntary association of over 10,000 biologists from around the world. In 1964 the IUCN’s Species Survival Commission established the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The Red List, as it is commonly known, tells us which plants and animals are in the greatest danger of extinction and whether our actions have improved or exacerbated their situation over time.

Over 100,000 species have been assessed since the List was established, and more are being added all the time. Although this extensive database is funded by a group of Red List partner organisations, the scientists involved in these assessments contribute to it for free. Assessments are made by the foremost experts on each species who rely on the latest scientific data and their own field experience to make their decisions. Besides assigning a species its conservation status, the assessment includes information about where it occurs in the world, what habitats it prefers, the threats it faces and what conservation actions are most needed.

Each expert assessment is then sent to recognised scientific authorities on the species in question (e.g. BirdLife International for birds) that review the assessment and confirm, challenge or reject any part of the initial assessment. Once an assessment passes the review process, the IUCN staff do a few quality control checks and post the final result on the Red List website, which is open to the public. If you want to know more about the conservation status of any species, simply enter its name in the search box.