Wildlife Research & Conservation Management Volunteer Projects in Africa

Live the life of a wildlife conservationist, helping to protect Africa’s legendary nature

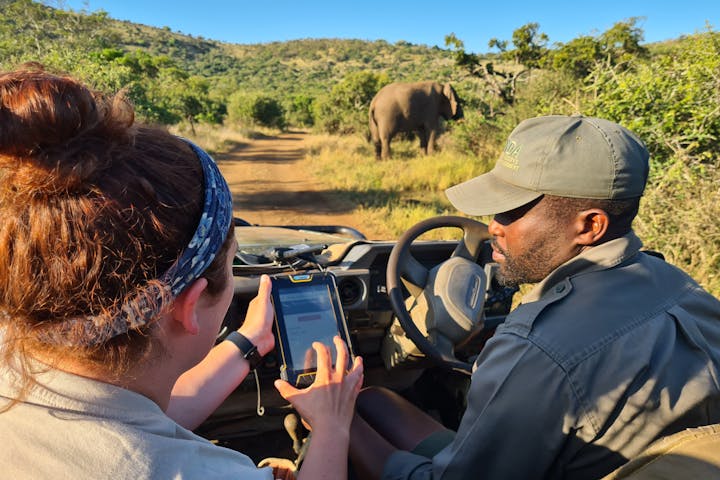

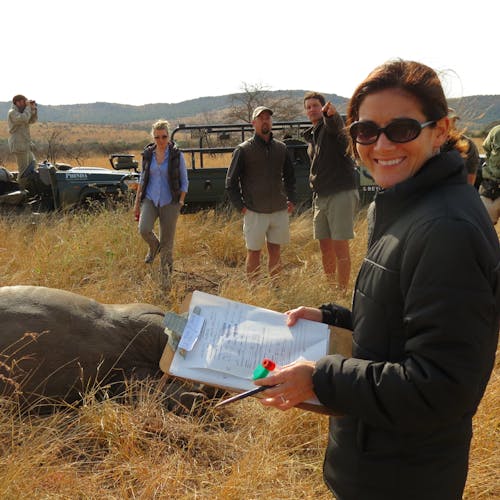

Walking in the footprints of elephants, learning to humanely relocate rhinos, then getting to grips with wildlife monitoring cameras… As a volunteer field researcher, you’ll spend your days exploring Africa’s untamed wilderness and your evenings sharing stories around the fire.

Why choose these experiences?

Whether you’re looking for a behind-the-scenes experience of Africa’s wildlife, taking the next step in your career or want to gain work experience in an African game reserve, these are the experiences for you. You’ll learn about habitat improvement, tracking animal movement, poaching prevention and more.

- Make a meaningful contribution to the future of Africa’s wildlife

- Track and monitor Africa’s wildlife in its natural habitat

- Work alongside experienced conservationists and species monitors

- Discover Africa’s beautiful ecosystems, away from tourist safaris

Choose Your Wildlife Research & Management Project

From Famous Kruger To Remote Okavango

Game Capture And Relocation Experience

Hanchi Horseback Project

Mangetti Wild Dog And Elephant Protection Project

Okavango Wilderness Project

Phinda Wildlife Research Project

The Vikela Kruger Conservation Experience

Traveller Stories

Conservation spotlight: wildlife research and management in southern Africa

Southern Africa’s wildlife populations are currently under threat from all sides. The region’s growing human population is placing ever more pressure on limited resources such as water and habitat, forcing wildlife to live on ever-shrinking ‘islands’ of land. Meanwhile, climate change is exacerbating the situation. Summers are getting hotter and lasting longer, affecting the flow of rivers that provide a vital supply of water for wildlife.

All of this is happening against a backdrop of poaching and big-game hunting, which is still legal throughout much of Africa.

Wildlife research and management underpin the region’s whole conservation movement. Every ecosystem is a delicate balance of species that hunt one another and consume natural resources such as vegetation and water. So to create a self-sustaining balance of species, conservationists need to constantly monitor the population dynamics of each animal, including ratios of male to female and age categorisations, how predator and prey species interact with each other and the available natural resources.

Carefully managed breeding programmes and the game-capture industry can help to re-establish lost wildlife populations.

Trophy hunting in southern Africa

At African Conservation Experience, we believe volunteering and conservation travel provide a viable financial model to replace trophy hunting.

While trophy hunting is still legally practised, we think the conservation community needs to continue its work identifying sustainable quotas for hunting. This is a vital task as trophy hunters predominantly focus on adult males, which raises serious questions about the impact on populations that are regularly exposed to hunting.

During your time in Africa, chances are you will meet people who strongly support or oppose hunting. From an outsider’s perspective, it is difficult to understand how anybody could defend a pastime which legitimises the killing of animals such as lions, elephants and rhinos. But this is a highly complex and controversial subject and the jury is still out on how best to manage trophy hunting in Africa.

As animal lovers and conservationists, it is important that we do not let our moral objections to trophy hunting cloud our scientific judgment. However, looking at all the facts, we believe that conservation travel represents a genuinely viable alternative to hunting — replacing the money provided by hunting licences with financial support from travellers who would rather help animals than hunt them.

Human-wildlife conflict in southern Africa

When you arrive in Africa, you’ll quickly discover one of the key issues affecting wildlife conservation is the expanding human population. This is resulting in more human-wildlife conflicts, leading to injuries and deaths on both sides.

The most common causes of human-wildlife conflict are animals damaging crops and livestock. When you consider that a fully grown elephant can eat up to 450kg of food a day, it’s easy to understand the farmer’s point of view. Similarly, if a pride of wild lions killed the herd of cattle you relied on for your livelihood, you might be tempted to use some pretty extreme methods to prevent a similar incident from happening again in future.

But there are ways to solve these issues that do not involve attacking or poisoning animals. Wildlife conservationists in Africa employ many different strategies to avoid human-animal conflict – and even find ways that people and wildlife can benefit each other. These include working with local communities to create physical barriers and deterrents as well as identifying ‘flashpoints’ such as a new electric fence which might cause animals to come closer to a town than normal.

The Phinda reserve in South Africa has succeeded not just in reducing conflict, but creating a positive working relationship between wildlife and humans. Once a private game reserve, Phinda is now owned by the local tribal community, providing a valuable source of income and employment. The knock-on effect is that the human population has become more appreciative of wildlife and the benefits that ecotourism brings.

From international politics to local projects

Many people ask why national governments aren’t doing more to protect threatened wildlife in their countries. Especially as ecotourism is such an important source of income for many of Africa’s poorest rural areas.

The most obvious answer is that governments in many developing economies simply don’t have enough money to invest in conservation. Even where governments have the desire to help, diverting funds away from programmes that target human poverty isn’t a politically viable option. Some governments in the region have introduced hunting bans, but these have caused as many problems as they’ve solved.

This is why the conservation projects we support are vital to preserve Africa’s wildlife and ecosystems. They bring targeted financial support to the conservation community and place a highly motivated workforce on the ground. Namely, you.

Explore other volunteering types

Adventure Learning Experiences

Gap Year Travel

Internships

Marine Conservation Projects

Sabbaticals & Career Breaks

School & College Field Trips

Short Experiences

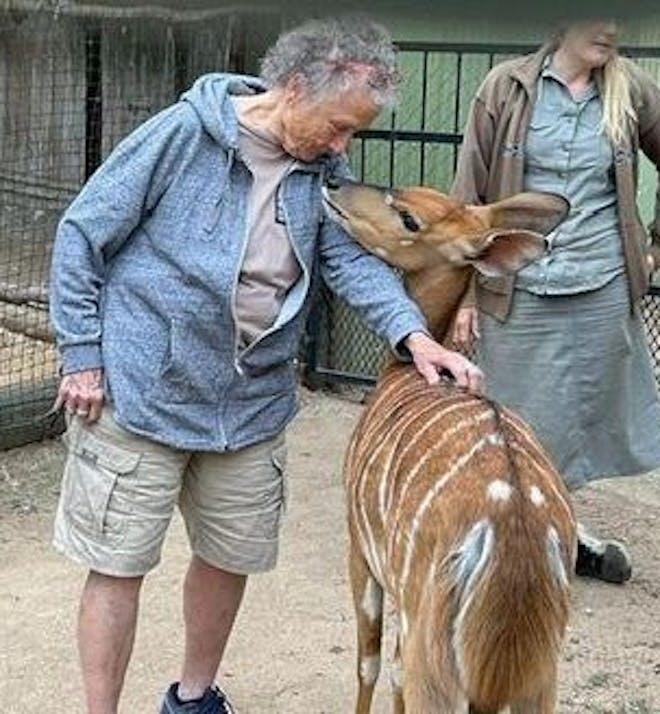

Wildlife Care & Rehabilitation

Wildlife Veterinary Projects

Or explore by animal

African Wild Dog Conservation Projects

Elephant Conservation Projects

Lion Conservation Projects

Rhino Conservation Projects